Here’s Why Internet Explorer’s Demise Is the Dawn of a New Era for the Web

Rest in Pieces, IE

Today web developers the world over are celebrating that, finally, mercifully, the end of life for Internet Explorer is upon us. With that, I felt it’d be good reminisce on the impact it had on the web over the 27 years it lasted. It was pretty bad, and here’s why.

When Microsoft Introduced Internet Explorer in 1995, as part of the “Plus! for Windows 95” add-on pack, the first browser war began, giving the then-dominant Netscape Navigator a run for its money. At that time, it was difficult and time-consuming for users to download and install browsers. It was beyond the ability (or desire) of typical computer users to download a browser, so having a web browser built right into the operating system that almost everyone used was incredibly convenient.

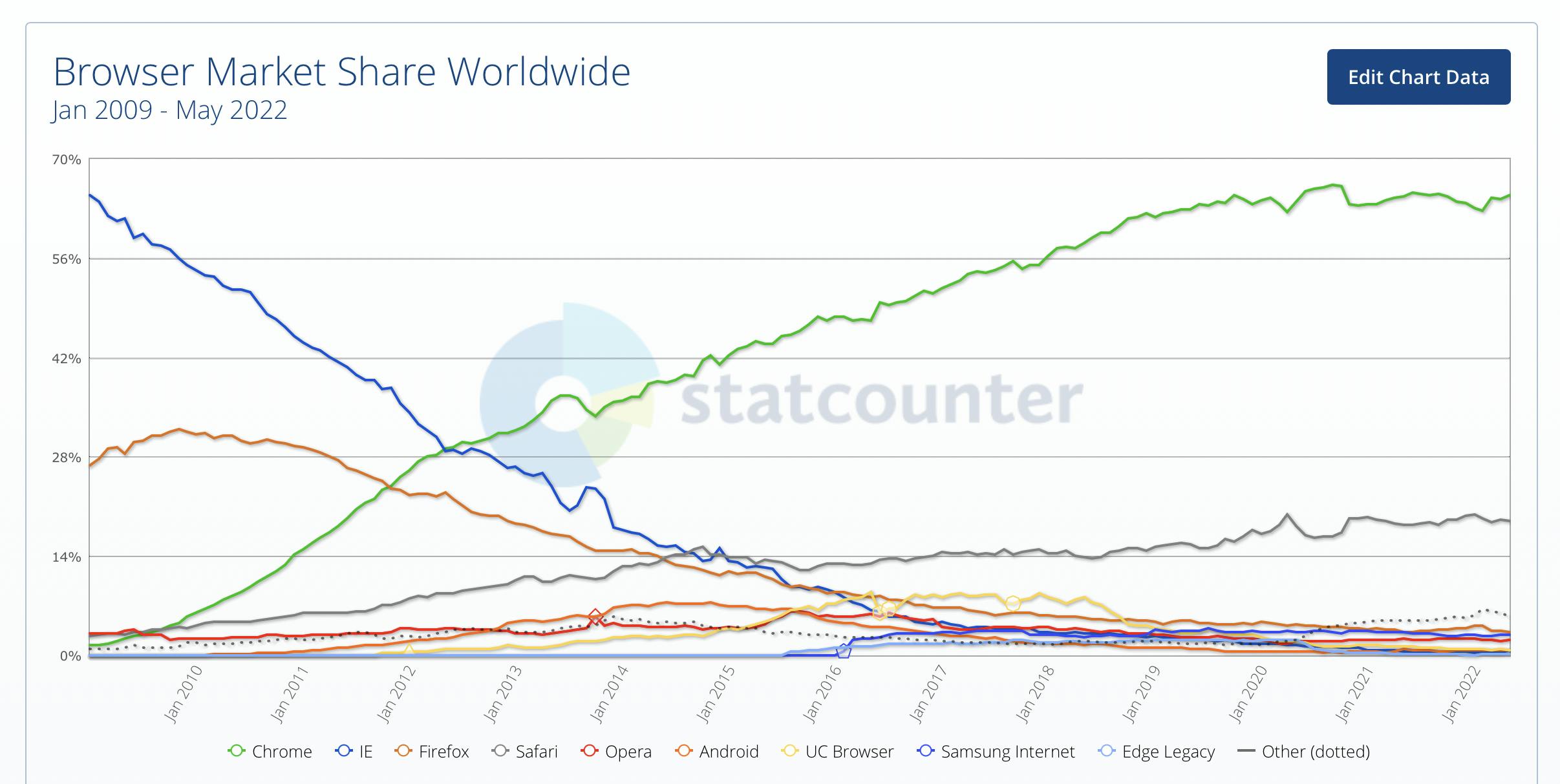

For the next several years through the lifespan of Windows 98 (and Windows XP), market share of Internet Explorer grew steadily, until it exceeded 94% in 2003, and Netscape Communicator became a faint memory before being discontinued in 2008.

At some point in the past, Internet Explorer was a pretty decent browser, comparing favorably to Netscape in many ways. The IE team even pioneered technologies like AJAX, (in IE 8). But overall, and especially with the release of Mozilla Firefox and continual improvements in the plucky Norwegian Opera browser (my favorite, back then), Internet Explorer fell behind.

The pace of innovation in Internet Explorer was incredibly slow over the years, with each version lagging far behind competitors in technological prowess. The browser itself was also slow as JavaScript became more important and other vendors found ways to speed up the browser, leaving IE completely in the dust in performance.

But none of that mattered at all. All that mattered was that a website had to work first and foremost in the browser that was enabled by default in the world’s most popular operating system. Unlike the earliest days of the web where websites would sport “Best viewed in Netscape 2.0” badges, you couldn’t be excused for making a website that wouldn’t work with Internet Explorer. And users just didn’t care much about web performance or standards compliance or other things. They just used what was included in the box. For the majority of computer users out there, “The Blue e” equaled the world wide web. People didn’t download and install browsers unless they were nerds.

This whole topic was the subject of a major antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft in 2000, but although there was a settlement, it didn’t seem to change the course of history very much.

It didn’t matter much at first when HTML5 and CSS3 was in early development, unleashing all manner of new capabilities for web developers… these features didn’t work in IE6 (despite that being a couple of versions old), which a significant percentage of people still used. Microsoft sometimes tied versions of IE not just to Windows, but to specific Windows versions. For example, the extremely popular Windows XP couldn’t install a version of IE higher than 8, so even once IE9 and IE10 were released, a large percentage of users were will running on IE8. This is the situation I found myself in when I started my current job where all the computers were stuck on Windows XP for the first few years. I couldn’t target a version of IE higher than 8. (Thankfully we have gotten much better and faster at upgrading Windows in our environment these days.)

A decade ago, web developers had to be very slow to adopt new front-end technologies because they just didn’t work in IE, and sometimes that’s the only browser people could use. IE wasn’t standards compliant and when businesses that built applications around proprietary features of IE, like ActiveX or its Windows integrations, users had no other option than to use IE.

I’ve been using the web since the early days (1994 or so), and I remember this time around the mid 2000’s feeling like a very dark time for the web. It felt like progress in web technology had ground to a halt. We depended on Adobe (née Macromedia) Flash for what little ability to play video we had, and that was another minefield. Making webpages that looked good and worked well was hard. It almost required you to make separate webpages for each version of a browser.

Sometimes you had to write weird code specifically for Internet Explorer that used these mutant HTML comments that would target specific versions.

<!--[if lt IE 7 ]>

<p>Only less than IE 7 will see this</p>

<![endif]-->

🤮!

I think few scenarios I’ve experienced in my lifetime so well illustrate the dangers of a monopoly controlling an important technology. It was terrible for the web and terrible for web developers. And in Canada (and to a lesser extent, the US), Internet Explorer enjoyed even higher market share than in the rest of the world.

Around 2009, things started to change. I went off to work for a small browser vendor called Opera, and Firefox had been enjoying some growth. In 2010, the EU started requiring Microsoft to push a “browser choice” screen that gave people the option to install a new browser that wasn’t IE as the result of more lawsuits against Microsoft.

But the big change was that Google was now a big and powerful company, and they decided that having a lousy web browser have a stranglehold on the market wasn’t going to serve their interests. They needed a good browser that was fast in order to make their products look and work better. Google wanted their web properties and their search engine front and center in the experience of the web. The best way for them to do that was to throw a ton of engineering talent at the problem, and a ton of money at marketing it, and thus Google Chrome was born.

It caught on like wildfire, with billboards and ads plastered everywhere. Google was now by far the dominant search engine, and Google.com pushed Chrome hard. The message was basically “Chrome is faster than crappy old IE” — and it really was (but so was every other browser that wasn’t IE). It worked. By now most people had broadband and fast Internet and fast computers so downloading and installing a browser wasn’t the tiresome task that it once was.

Over the years since then, Chrome ate away at market share for other browsers. And at the same time, smartphones exploded in popularity, with mobile usage of some websites eventually catching up to desktop browsers. IE just wasn’t a player in this space at all, especially since Microsoft’s attempts at creating a mobile platform failed miserably.

Today the only two browsers that matter in any significant way are Chrome and (to a much lesser extent) Safari. Perhaps this is again a sorry state of affairs, because we again have an almost monopoly situation, and Chrome and Safari originally were both originated from the Webkit project (although Chrome forked into Blink around 2013 because they didn’t like having to agree with Apple on the direction of Webkit).

Almost every other browser on the market (including the newer versions of Edge, Opera, Samsung Internet, Brave, etc.) are derived from the Chromium open source project, which is the core of Chrome itself. But despite the near-monopoly situation we again find ourselves in, it is clear that Google is a much better custodian of this important web technology than Microsoft was.

With IE usage down to negligible levels, and Internet Explorer finally being discontinued, that means that almost every browser in active use is a modern browser that is routinely kept up to date, and not contingent on the glacial pace of Windows releases. When a web technology is rolled out in a new browser version, web developers can start using it immediately and not wait until the computers running older browsers are retired and shipped to landfills.

This is a very exciting time to be a web developer and a creator on the web because the pace of innovation, change, and evolution is blinding. That opens up so many possibilities that weren’t possible when over two-thirds of web users were running Internet Explorer.

So goodbye Internet Explorer. You won’t be missed by the likes of us developers.